Reconstructing a Lost Holocaust Family

by Carole Garbuny Vogel

This article was originally published in Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy, Volume XXII. No. 1, Spring 2006.

Changes have been made in red to reflect information learned after this article was first published. Additionally, photographs from Jonathan Burg of London have been added as well as a few relevant images from CGV’s collection.

For more than 30 years I have been trying to reconstruct the family of my grandfather, Dr. Moriz Löwy, a Viennese pediatrician. Moriz was part of a huge and close-knit extended Jewish family that had made the region of western Hungary and eastern Austria their home for more than 600 years. His ancestors had fled the Spanish Inquisition and in 1336 started the Jewish community of Mattersdorf, Hungary (now Mattersburg, Austria). In 1938, shortly after the Nazis seized power in Austria, my grandfather escaped with his wife and children, first to France then to England and the United States. Some of his relatives also found refuge outside of Nazi Europe, but most were stranded within.

My grandfather Dr. Moriz Lowy with his wife and children in June 1939, shortly after they arrived in New York City. I am certain that he sent a copy of this photo to his mother and sister who remained in Vienna.

I wanted to learn what happened to all of Moriz’s relatives who had been in Europe at the beginning of the Holocaust. But how could I identify and document the fate of more than a hundred people whose names I did not know and who had vanished without a trace? If survivors could be identified, how could I find them or their descendants? Göteborg, Havana, Jerusalem, Rio de Janeiro, and Shanghai were just a few of the places where family members initially had fled.

At first, I couldn’t even account for the whereabouts of Moriz’s own sister Frieda Löwy Sipser, who had survived the war, or of his mother who had perished. More than two decades later, I have not only documented their experiences but I have also discovered the fate of more than 400 of Moriz’s relatives.

Moriz’s brother Adolf Heinrich Löwy (1887-1972) fled to Palestine, their father Max Löwy (1859-1929) died of natural causes before the war, and mother Franziska Löwy née Kohn (1867-1943) who died of starvation and typhus in Theresienstadt Concentration Camp.

Starting the Research

Beginning in 1979, twenty years after my grandfather’s death, I contacted every surviving family member about whom I knew and pumped them for information. I diligently recorded names, places, and anecdotes, and always asked for contact information for other survivors or their children. In this way, I found branches of my family scattered all over the world: Argentina, Austria, Australia, Brazil, England, Israel, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, even in East Berlin in the then DDR. I also discovered that people who married into the family were sometimes more knowledgeable about the family history than blood relatives.

I was able to learn the identities of most of my grandfather’s aunts, uncles, first cousins, and some second cousins, and at least established whether or not they had been murdered. I learned that Moriz’s mother, Franziska Kohn Löwy, had perished in Theresienstadt concentration camp, and that his sister Frieda had been confined in a War Relocation Authority detention camp in Oswego, New York. (See: “Oswego, New York: Wartime Haven for Jewish Refugees,” published in Avotaynu, Winter 1998, for a detailed description of I how traced Frieda’s wartime prisons and sanctuaries in Italy, and with the help of the U.S. Embassy at the Vatican, located the Italian families who had hidden her from the Germans.)

Moriz’s sister Frieda Sipser née Löwy fled to Italy during the Holocaust.

After depleting family resources, I turned to Project Search: The Holocaust and War Victims Tracing Service run by the American Red Cross, and requested information on 39 specific relatives of Moriz’s who had perished. Project Search in turn contacted the International Tracing Service in Arolsen, Germany, which is the largest repository of Nazi documentation in the world. Project Search also queried the national Red Cross societies of Austria, France, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia on my behalf, and looked into other sources. Over the course of a few years, Project Search provided answers for about half the people on my list, including Moriz’s mother. It provided her birth date, last address in Vienna, the date of her deportation to Theresienstadt, and date of her death.

In the book Totenbuch Theresienstadt I: Deportierte aus Österreich (Death Book Theresienstadt I: Deportation from Austria) (Wien: Herausgeber: Jüdisches Komite, für Theresienstadt, 1971) I found more than a dozen family members who had been deported to Theresienstadt. Beit Theresienstadt, the Theresienstadt Martyrs Remembrance Association in Givat Chaim-Ichud, Israel, supplied photocopies of their inmate records. The records gave the transport number and arrival date in Theresienstadt and sometimes the date of death and cremation. In the cases where the victims were sent to their death at other extermination centers, the transport information was also noted.

Memorial to the Jews Deported from France by Serge Klarsfeld, (Paris: 1983) revealed that Moriz’s cousin, Dr. Ignatz Deutsch, had been deported to Auschwitz with his wife and 10-year-old daughter on September 9, 1942. All the victim information in Klarsfeld’s book and in the Theresienstadt records is now included in the Yad Vashem database.

Search for family took me to the metrical records of the Jewish community of Nagymárton (the Hungarian name for Moriz’s ancestral town, Mattersburg, Austria), which I accessed on microfilm through the (Mormon) Family History Library. Using the microfilms, I traced all the branches of Moriz’s family back to the late 1700s or early 1800s, and then forward again. The records ended in 1921 so I obtained a substantial picture of the family branches that had stayed in Mattersburg.

Many family members, however, had taken advantage of changes in Austrian law in the mid-1800s that permitted Jews to settle throughout the Austria-Hungarian Empire instead of being restricted to a limited number of towns. Moriz’s paternal grandparents moved to Gloggnitz, and his maternal grandparents settled in Baden bei Wien, both in Lower Austria.

Collaboration with Other Researchers

In 1989, after learning that the synagogue in Baden was functional, I wrote a letter asking if anybody remembered my family. This was the beginning of a wonderful friendship with Thomas E. Shärf, the president of the Jüdischer Synagogenverein in Baden, the last remaining Jewish community in Lower Austria. Thomas was researching the Jews of Baden and could access local and national archives in Austria. I had photographs of the family, contact information, and the family history. We shared information freely. Although no synagogue records survive, in the Israelitische Kultusgmeinde Wien (IKG), the headquarters of the Vienna Jewish Community, Thomas located the Matrikel (vital record) books of the Jewish Community of Baden volumes I and II, (1837-78 and 1878-1937). Each book, a cross between a household registration book and birth register, provides birth information (not always accurate), as well as marriage and death records for Jews who had lived in Baden. Volume I has many gaps.

In the district court of Baden, Thomas found the Grundbuch (land book) for Baden so he was able to trace the history of the property owned by my family.

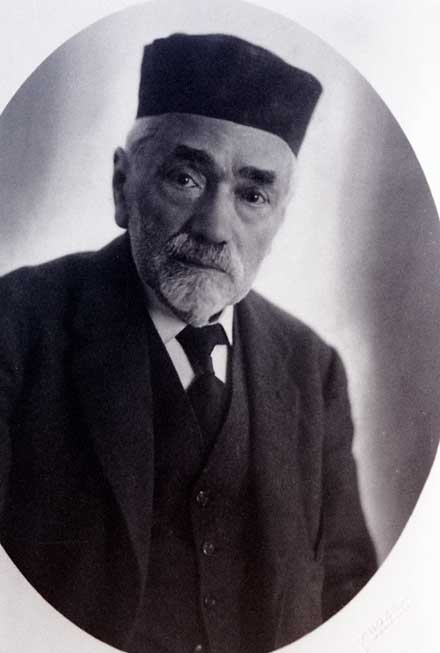

Moriz’s grandfather, Jakob Kohn (1839-1927)

Among Thomas’s many other incredible finds were the last will and testament of Moriz’s grandfather Jakob Kohn (1839-1927), and correspondence between Moriz’s brother Adolf Heinrich Löwy and the Nazi authorities in Austria. The latter dealt with the confiscation of the assets of the Bethaus (house of prayer) in Gloggnitz, the village in Lower Austria where Moriz had been raised and where his brother still lived. Adolf had already surrendered the savings book of the Bethaus to the Gloggnitz SA but requested in writing that the money in the account be used for a charity to benefit the needy people of Gloggnitz. This request generated much correspondence between the SA in Gloggnitz and various Nazi organizations in Vienna. Here is a translation of one of the memos:

Among Thomas’s many other incredible finds were the last will and testament of Moriz’s grandfather Jakob Kohn (1839-1927), and correspondence between Moriz’s brother Adolf Heinrich Löwy and the Nazi authorities in Austria. The latter dealt with the confiscation of the assets of the Bethaus (house of prayer) in Gloggnitz, the village in Lower Austria where Moriz had been raised and where his brother still lived. Adolf had already surrendered the savings book of the Bethaus to the Gloggnitz SA but requested in writing that the money in the account be used for a charity to benefit the needy people of Gloggnitz. This request generated much correspondence between the SA in Gloggnitz and various Nazi organizations in Vienna. Here is a translation of one of the memos:

It took until January 15, 1940 for the case to be officially closed and the request denied. Thomas found these incredible Nazi-era documents in the in the Stillhaltekommissar files of the Archiv der Republik und Zwischenarchiv (Archive of the Republic) located in the Österreichisches Staatsarchiv (Austrian State Archive) in Vienna.

I had another fruitful relationship with a researcher from another town in Lower Austria. Gerhard Milchram, a curator at the Jüdischen Mueseum der Stadt Wien (Jewish Museum of Vienna), who was writing the history of the Jewish community of Neunkirchen, the large town where Moriz’s uncle Simon Löwy had lived. Gerhard provided me with the names, birth dates, professions, and addresses of family members in Neunkirchen, including information on children. This was quite a feat because the local Nazis in Neunkirchen had deliberately set the town hall on fire near the end of the war. The resulting blaze destroyed the birth, marriage, and death records of the Jews of Neunkirchen and surrounding villages, including those of my grandfather’s immediate family and many of his Löwy cousins.

This feat, however, was a minor miracle compared to what followed: For many of the victims Gerhard identified the ghetto or concentration camp where he or she had been deported. For most of the survivors he was able to tell me to which country they had immigrated.

The research efforts of both Gerhard and Thomas have resulted in the publication of two magnificent books: Heilige Gemeinde Neunkirchen: Eine jüdische Heimatgeschichte (The Holy Community of Neunkirchen: A Jewish Local History) by Gerhard Milchram (Wien: Mandelbaum Verlag 2000) and Jüdisches Leben in Baden: Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart (Jewish Life in Baden: From Its Early Beginning until the Present) by Thomas E. Shärf (Wien: Mandelbaum Verlag 2005). A bonus for me is that my family is discussed in both, and Gerhard even devoted an entire chapter to the Löwy in Gloggnitz.

Gerhard had found my name in JewishGen’s Family Finder (JGFF) (www.jewishgen.org/jgff). Even before connecting with Gerhard, The JGFF had already become one of my most valuable research tools. I had discovered it in its pre-website form, the Jewish Genealogical Family Finder, a computer database list published by Avotaynu that was distributed to all Jewish Genealogical societies and made available during the societies’ meetings. The JGFF provides the family names and towns researched by genealogists, along with contact information.

I have met several long-lost relatives using this amazing tool. The most profound interaction was from a man named Deutsch who been born in 1938 and survived the war in hiding in Belgium with his mother. His father survived Auschwitz, and after the family was reunited post-war they immigrated to Australia. The father refused to talk about the past and they had been able to locate only one other branch of the family. As far as Mr. Deutsch knew the rest of the entire extended family had been annihilated. Not only was I delighted to tell him that his father and my grandfather were second cousins, but I was able to trace the family back for him to the late 1700s, show him that he had relatives all over the world, and connect him with several other surviving branches of the family living in Australia. They held a family “round up” in his honor.

Archives in Vienna

The IKG Wien is the repository for the birth, marriage and death records of the Vienna Jewish community. In 2005, I visited the archives and found the vital records for two- dozen relatives, including the marriage record of my grandparents and the birth records of their three children. Death records of four of Moriz’s distant cousins were especially useful because the death dates and last home address of the deceased were keys to unlocking information at other archives.

The Österreich Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library) holds microfilms of the Neues Wiener Tageblatt and the Neue Freie Presse, two newspapers in which Jewish families placed obituaries. Knowing the death dates allowed me to find the death notices for two of the cousins. These obituaries provided the names of the decedents’ surviving children and grandchildren.

At the Wiener Stadt und Landesarchiv (Vienna city archives), I needed the death date and last address of the deceased to locate probate records. Like death notices, probate records provided the names of survivors but were even more useful because they also gave the ages of all the children, included the addresses for some, and gave the names and places of residence of the other nearest relatives or heirs mentioned in the will. In this archive I also found Meldezettel (household registration records) for my grandfather and a few of his relatives. These Meldezettel showed every address where they had lived and when, furnished the birth date and place, profession, names of the spouse and children, religion, departure date and place, which in some cases were death or deportation dates. My grandfather’s record showed that he left Vienna for France in July 1938.

I visited the Österreichische Staatsarchiv Kriegsarchiv (Austrian war archive) and with the help of an extraordinarily helpful archivist I reviewed the Stellungslisten (enlistment registers) for the Burgenland Bezirk (military district) of Mattersburg. In 1868, a universal conscription had been instituted in the Austrio-Hungarian Empire and all able-bodied men, regardless of religion, were obligated to serve three years of active duty. (In 1912, the requirement for active duty was reduced to two years.) Starting with the birth year of 1867 and going into the early 1890s, there was a Mattersburg Stellungslisten for nearly every year.

The Stellungslisten contain far more than draft registration information. They supply the birth year and place, name of father (and sometimes the mother’s name, occasionally with the maiden name), occupation, information about the actual service of each soldier and more. The information in the Stellungslisten can be used as a compass to find other service records. From Moriz’s World War I service record, I learned that he had served beyond the call of duty and had been nominated for the Goldenes Kreuz (gold cross).

Many of the men listed in the Stellungslisten ledgers of Mattersburg were born elsewhere and/or lived in other places. The key to being listed was the father’s citizenship. From these records I was able to identify cousins of Moriz’s who had been born in Italy, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. It is unlikely that I ever would have discovered most of these individuals elsewhere.

Online Resources

The usefulness of the JewishGen website in Holocaust research cannot be overstated. In addition to the JGFF, JewishGen posts the Family Tree of the Jewish People (a searchable compilation of family trees of Jewish researchers), the JewishGen Holocaust Database (with more than a million entries related to Holocaust victims) the Yizkor Book Necrology Database (with more than 170,000 entries of victims), and much more.

The Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes (Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance [DÖW], www.doew.at) has a searchable database with more than 62,000 Shoah victims from Austria. This site is useful for finding family groups; parents and their children were typically herded into ghettos or dispatched to concentration camps together. Consequently, it is a depressing research vehicle to use.

The most depressing but also most useful website for Holocaust research by far is the one sponsored by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem. (www.yadvashem.org) For nearly 50 years, Yad Vashem has been registering the names of Shoah victims in Pages of Testimony, which serve in lieu of gravestones for those who perished. To identify specific victims, Pages of Testimony are designed to provide personal details, such as parents’ names, date and place of birth, name of spouse and children, profession, residence before and during the war, as well as the fate of the individual. I have found far too many of my relatives in this memorial and sadly have discovered that often there is no Page of Testimony for relatives who were killed. The last step in reconstructing my family is to fill out a Page of Testimony for each victim.

Case Study: The Schotten Family

The following shows how I reconstructed the extended family of Moriz’s paternal grandmother Regina Österreicher Löwy (1822-1900), the daughter of Simon Moses Österreicher and Rosalia Holzer. In the metrical records of the Jewish community of Nagymárton/Mattersburg (which I accessed on FHL microfilm), I was able to identify only one sibling of Regina’s—Johanna Oesterreicher (1837- 1904). In 1868, Johanna married Jakob Goldberger, the son of Sebastian Goldberger, and had at least three children:

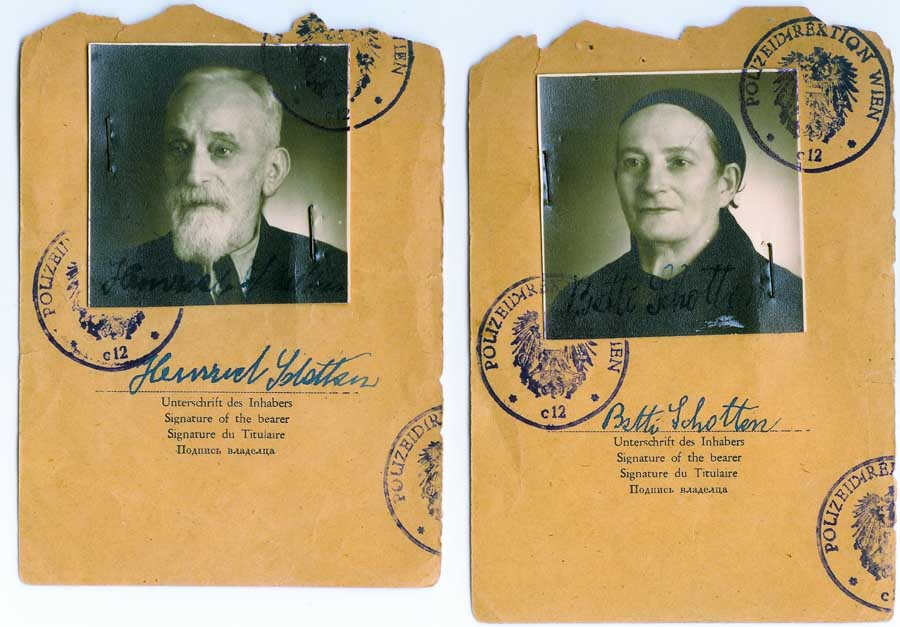

- Berta (Betti/Blumele) Goldberger was born in 1875, and at age 19 she married Heinrich (Chaim Yeshaiya) Schotten, who was likely her cousin. He was the son of Samuel (Shmuel Aron) Schotten and Kati (Gela) Oesterreicher.

- Katalyn Goldberger was born in 1879, and became the wife of Salamon Pollack in 1907.

- Simon Goldberger was born in 1871.

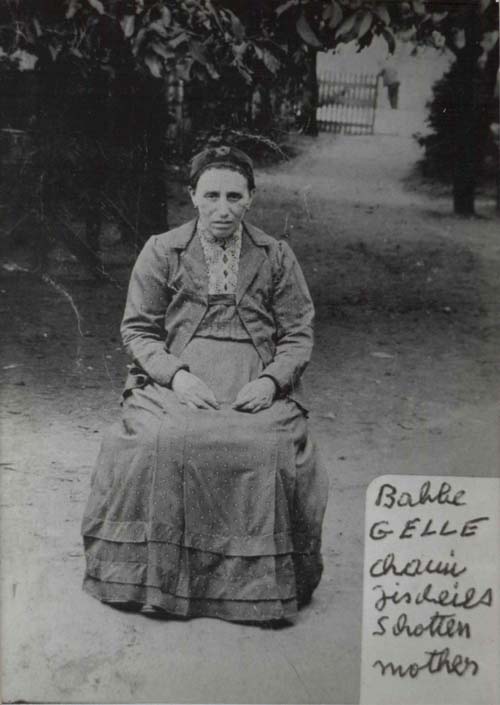

Johanna Goldberger née Oesterreicher (1837-1904) mother of Betti/Blumele

Kati (Gela) Schotten née Oesterreicher was likely a cousin or perhaps even a sister of Johanna Goldberger née Oesterreicher. So far I have been unsuccessful in learning the names of her parents.

Berta (Betti/Blumele) Schotten née Goldberger

Heinrich Schotten’s Hebrew name was Chaim Yeshaiya but initially I had been told it was Chaim Yishai. This confused me because one of his brothers was Josef (Yishai) and in Jewish tradition two brothers cannot have the same name unless one of them died before the other was born.

Blumele Goldberger and Chaim Schotten’s children

Blumele and Chaim were quite prolific. Beginning with the arrival of their son Jakob Schotten on 16 Feb 1896 and ending with the birth of their daughter Gizella on 24 Nov 1913, they produced twelve children. I learned much later that there was a thirteenth child, the eldest: Rosa Schotten, who was born in 1895.

The Schotten children who appeared in the Mattersdorf metrical records:

1. Jakob Schotten (16 Feb 1896)

2. Ignatz Schotten (22 Jul 1897)

3. Malvine Schotten (13 Sep 1898)

4. Siegmund Schotten (18 Nov 1899)

5. Helen Schotten (11 Jan 1901)

6. Irma Schotten (12 May 1902)

7. Moritz Schotten (10 Aug 1904)

8. Johanna Schotten (16 Nov 1905)

9. Ester Schotten (12 Dec 1907)

10. Sofia Schotten (29 Apr 1910)

11. Anna Schotten (3 Jul 1911)

12. Gizella Schotten (24 Nov 1913)

Plus Rosa Schotten makes 13. Her birth record is not found in the Mattersdorf metrical records.

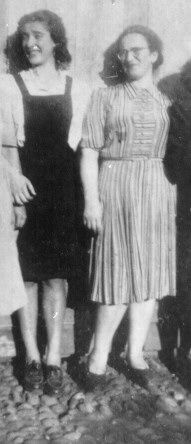

The Schotten daughters in happier times. Right to left (front): A cousin, Johanna/Chana/Janka, Sophie, Esther, Irma, (Back row): Malvine and Menachem Lipschutz (her husband); At the tree – a cousin’s daughter

All but two reached adulthood: Moritz died about a month after his first birthday, and Gizella, the youngest, died in 1916, at the age of 2½.[i] I had the sense that the Schottens adhered to Jewish tradition more closely than my more secularized grandfather, who had practiced family planning and fathered only three children.

I shared my list of Schotten names with my grandfather’s cousin, Joseph Spiegel, whom I had discovered in St, Louis a few years into my project. I figured that by the time of the Anschluss(annexation of Austria by Germany) in 1938, most of the surviving Schotten children would have been married and had young families of their own. I hoped that Joseph could tell me what had happened to the family and how to contact them. I didn’t anticipate his reply:

“The deportations in Vienna were going on fast and furious and my mother and [sister] Regina moved from one place to another. Mr. Schotten and his wife stayed in Vienna at that time. He had some connections to help people cross the border into Hungary and he approached my mother to avail herself of this help, but for a time she did not dare accept his offer. One day, Mr. Schotten warned my mother that to wait any further would jeopardize her existence. Regina and my mother left the next day. A Hungarian farmer’s wife showed up and took them across the border…The sad part of the story is that Mr. Schotten got his own children across the border into Hungary but they were later deported and never heard from again. Chaim and Blumele Schotten were later deported to Theresienstadt but survived and lived in New York…”[ii]

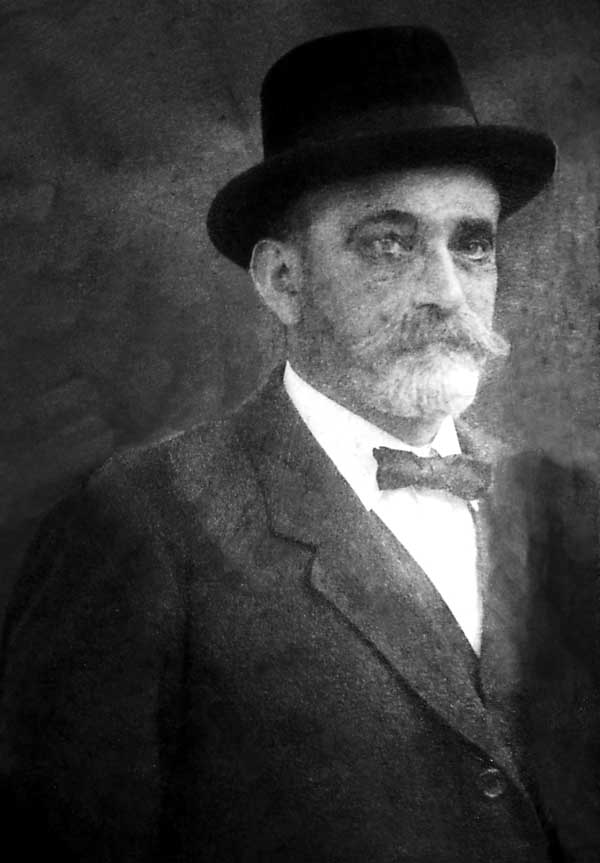

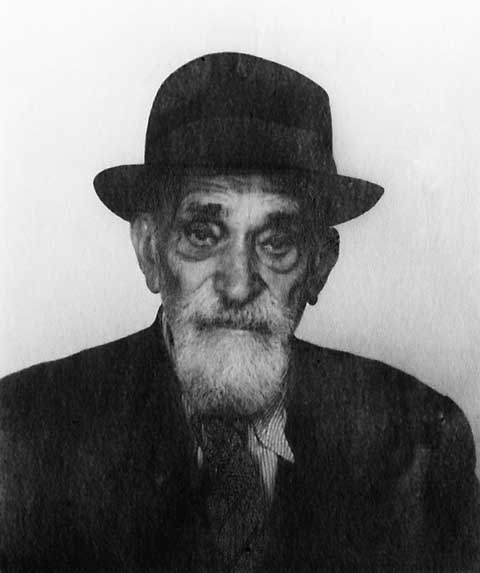

Photograph of Heinrich Schotten taken circa 1935, about five or six years before he was deported to Theresienstadt.

I cannot imagine anything more tragic than a parent losing a child, yet alone ten of them. Suddenly my hunt for long-lost relatives took on a most somber note and instead of planning a joyful family reunion I began the sad task of documenting the lives and deaths of the Schotten children. I was unable to make much progress until recently when Yad Vashem Pages of Testimony and other Holocaust records became available online. The happiness that I had experienced 20 years ago with the discovery of each new Schotten child in the Mattersdorf birth records was now being matched with the despair of finding proof of their murders.

[i] Gizella Schotten death record. Date of death: 4 Mar 1916. Age: 2 (born circa 1912). Birthplace: Mattersdorf. Place of death: Mattersdorf. Parents: Heinrich Schotten and Betti Goldberger. Cause of death: göresök [görcs means spasm]. Death reported by her mother on 5 Mar. Nagymárton death registrations 1902-1920, FHL microfilm 0700405, p. 2 entry 11. [Researched by CGV 2006]

[ii] Letter from Joseph Spiegel; St. Louis, MO to C.G. Vogel17 Dec 1990.

Fate of the Schotten’s daughters:

1. The eldest daughter was Rosa (Chaya Sara) Schotten (born 1895). I did not learn of her existence until late in the research process. Her fate is discussed later.

2. The second daughter, Malvine Schotten (born 1898), married Emanuel Lipshütz of Deutschkreuz, Austria, and they made their home in Mattersburg. During the Holocaust, they fled to France. Emanuel was captured in Paris and deported to Auschwitz on 22 Jun 1942. He perished there a few weeks later on 10 July 1942.[i] Malvine hid in southern France near the Spanish border with her teenage daughter Vera Lipshütz (born 29 Dec 1925). They were captured and deported to Auschwitz on 9 Sep 1942.[ii] [iii] Malvine had one daughter who survived the war and submitted pages of testimony for Malvine and Vera at Yad Vashem.[iv] She gave her name and address as Herma Migliavacca of Milan, Italy, but I was unable to contact her. I later learned that Herma had married an Italian man who was quite older than she and a functionary of the Italian Communist party. They had a daughter. During the war Herma was hidden by her husband’s family. It is not clear whether she married during or after the war. Unfortunately, Herma had already died by the time I learned of her existence.

Malvine Schotten and Emanuel Lipshütz had a third child– a son, Hashy Lipshütz—whom I also learned about late in my research. He is discussed later.

3. The third daughter, Helene Schotten (born 1901) lived at Schmelzgasse 9, in Vienna during the Shoah, I learned her married name—Nichtburg—from the DÖW website and a Page of Testimony submitted in 1999 by Pnina Horowitz of Jerusalem who identified herself as a niece.[v] [vi] From this I could not tell whether Pnina was a niece by blood or marriage. Helene’s son, Beno (Gershon Baruch) Nichtburg shared the same address as Helene but there was no information about Helene’s husband or other possible children.[vii] At some point Helene and Gershon Baruch escaped to Hungary, undoubtedly with the aid of Helene’s father. The boy apparently died in an internment camp in Budapest. Helene was deported from Hungary to Auschwitz concentration camp on 5 July 1944. (More later)

Portrait of Helene (Rochel Leah) Nichtburg née Schotten

4. Irma Schotten (born 1902) married Deszö (Desiderius) Weisz, and they made their home with their two children in the second district of Vienna, on Taborstrasse, the same street where my grandfather had lived. During the Holocaust, Irma, her husband, and daughter Hilda (born 1927), fled to Italy where they were interned in a labor camp in northern Italy by the Italian fascists. When the Germans took over northern Italy in Fall 1943, the family was arrested in Livorno Ferraris, a municipality in the Piedmont region in the northwestern part of the country. The were sent to San Vittore Prison in Milan, and from there in 1944, they were deported to Auschwitz, where Deszö and Hilda died. [viii] [ix] Irma was transferred from Auschwitz to Stutthof concentration camp, where she perished.[x] A Page of Testimony by Pnina Horowitz revealed that Irma had a child who survived.[xi] I didn’t know the child’s name or whereabouts during the war but I was able to track him down after I published this article. His name was Ottfried Weisz (more later). I deduced from Irma’s Page of Testimony that Pnina was a blood relative but I was unable to reach her.

Irma Weisz née Schotten with her daughter Hilda, circa 1936.

Hilda Weisz, circa 1935

Deszö (Desiderius) Weisz, circa 1935

Deszö Weisz with his children Hilda and Ottfried, 1936.

5. Pnina also submitted a Page of Testimony for Janka Schotten (born 1905).[xii] Pnina apparently did not know Janka’s married name—Johanna (Chana) Schwarz—or that Janka/Chana had one son who survived the Holocaust and one who perished. (More later) From the DÖW website I learned that Chana had lived with her parents in Vienna during wartime, fled to Hungary (with the help of her father), and was deported to Auschwitz on 5 July 1944, the same day as her sister Helene.[xiii]

Janka (Chana) Schwarz née Schotten.

6. Esther Schotten (born 1907) was also remembered in a Page of Testimony submitted by Pnina, but the tribute did not include any mention of a husband or children, or Esther’s whereabouts during wartime.[xiv]

7. Sofia Schotten (born 1910) also seemed to have disappeared without a trace but was remembered by Pnina who submitted a Page of Testimony for her. (More later)

[i] Emanuel Lipshütz entry. Death Books from Auschwitz: Remnants. Reports edited by State Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau. (München: K.G. Saur, 1995.), p. 14682/1942. <Yad Vashem online>3 Malvina Lipschutz née Schotten entry. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum French Deportation List, p. 58, line 109. < USHMM online>

[iii] Vera Lipshütz entry. Memorial de la deportation des juifes de france by Beate et Serge Klarsfeld, Paris: 1978. Transport 30 from Drancy to Auschwitz. <Yad Vashem online>

[iv] Vera Lipshütz and Malvine Lipshütz neé Schotten Pages of Testimony. Submitted by Herma Migliavacca neé Lipshütz <Yad Vashem online>

[v] Helene Nichtburg neé Schotten entry. List of Victims from Austria. Namentliche Erfassung der österreichischen Holocaustopfer Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes, DÖW, Wien. <DÖW online>

[vi] Helene Nichtburg neé Schotten Page of Testimony submitted by Pnina Horowitz neé Schotten, 1999. <Yad Vashem online>

[vii] Beno Nichtburg entry. List of Victims from Austria < DÖW online>

[viii] Irma Weisz neé Schotten Page of Testimony submitted by Pnina Horowitz neé Schotten, 1999. <Yad Vashem online>

[ix] Dezö (Desiderius) Weisz and Hilda Weisz Pages of Testimony submitted by Pnina Horowitz neé Schotten, 1999. <Yad Vashem online>

[x] Irma Weisz neé Schotten entry. German Jews at Stutthof concentration camp listing. <JewishGen Holocaust Database Online>

[xi] Irma Weisz neé Schotten Page of Testimony <Yad Vashem online>

[xii] Janka Schotten Page of Testimony <Yad Vashem online>

[xiii] Johanna Schwartz entry. List of Victims from Austria. < DÖW online>

[xiv] Esther Schotten Page of Testimony <Yad Vashem online>

Fate of the Sons

Although I had no trouble documenting the deaths of six of Chaim and Blumele’s daughters, I could find no information on their sons. Was it possible that Joseph Spiegel had been wrong, that at least two or three of the Schotten children had survived the Shoah? I cast my nets wider, and I found Sigmund Schotten in the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) and found an exact match with his birth date—18 Nov 1899. I sent for his social security application, which he had filed on 1 Mar 1939, while living on Long Island. It showed that his parents indeed were Heinrich Schotten and Betty Goldberger. Sigmund died in December 1960.

Also listed in the SSDI was his brother, Ignatz Schotten (born 1897). Ignatz’s Social Security Application, which was filed in June 1950 from New York City, showed that he was employed by Mentor Watch Company on West 42nd Street (near Times Square). I later found out that Ignatz owned the company and had hired people to sell and repair watches. Ignatz would fly to Switzerland and purchase run-of-the-mill Swiss watches, 10,000 to 15,000 at a time. Before the Holocaust, Ignatz had repaired watches and clock tower timepieces in Vienna. He must have been quite skilled.

Ignatz Schotten

So at least the Schottens were not completely bereft of close family. They had two sons to bolster their spirits when they moved to New York City after the war. Still unaccounted for were the Schotten’s oldest son, Jakob (born 1896) and second youngest daughter, Anna (born 1911), and their oldest daughter Rosa (born 1895).

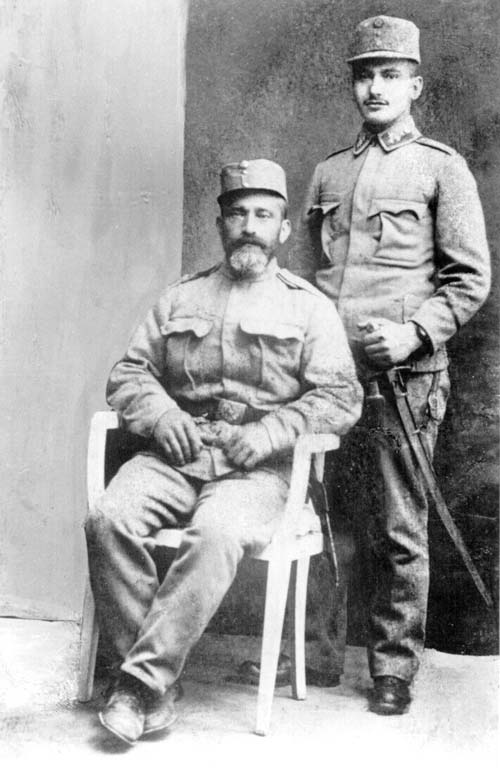

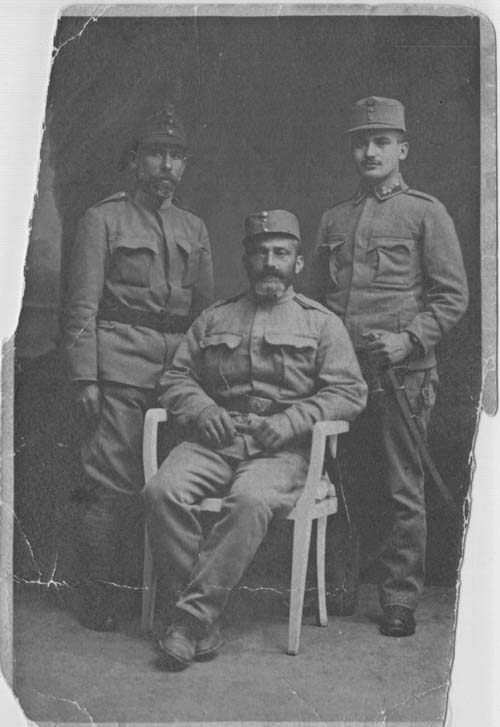

Heinrich and his eldest son Jakob Schotten, circa 1916. Apparently both Schottens were called up to fight for their king and country during World War I. Men from Mattersdorf served in the Hungarian army, not the Austrian. The photo was made from the image below

The man who was cut from picture was supposedly a friend of the family, and likely from Mattersdorf.

While perusing Ancestry.com in September 2005 for more Schottens, I came across two message board postings of interest. One dated April 1999, was from a Jonathan Hall, seeking information about Irma Maria Schotten who had married Desiderius Weisz. A definite match for “my” Schotten family, but I worried that his email address might be obsolete.

Irma Schotten, circa 1935.

Johanna (Chana) Schotten Schwarz

The other posting, a response to Hall, had been placed only 3 weeks earlier by a Jonathan Burg. I sent Jonathan an email message and learned that he had never heard from Hall. This didn’t matter (or so I thought). Jonathan was a great-grandson of Chaim and Blumele and he held most of the answers I was seeking. His father, David Nichtburg, was one of Helene’s three other children (all previously unknown to me) who had all survived the war.

During my original research I was amazed at the number of Schottens whose wartime address was listed as Schmelzgasse 9, the home of Chaim and Blumele in Vienna. I later learned that the apartment had been leased by Deszö (Desiderius) Weisz, Irma Schotten’s husband. I realized that having so many “guests” was not a matter of hospitality but of necessity forced upon the Schottens because of the severe shortage of housing for Jews created by the Nazis. Jonathan confirmed that the apartment had been extremely cramped, with 39-42 relatives. Some of them were the Schotten’s children and grandchildren. But also sharing these tight quarters were Chaim’s widowed sister Rosalia Holzer (born 1875) and two sons of Chaim’s other sister, Hermine Weiss. The first son, Josef Weiss (born 1897) stayed until his deportation to the Opole ghetto on 15 Feb 1941.[i] The second son, Max Weiss, lived there with his wife and five children (all under age 10) until the Nazis deported the family to the Izbica ghetto in Poland on 5 Jun 1942 [ii] Deported with them was Gitta Schotten (born 1904), who might have been Josef’s wife.[iii] The widow Holzer was deported to Theresienstadt on 21 Jun 1942, the same day that Chaim and Blume were sent there. Mrs. Holzer was later transferred to the Lodz Ghetto and her death.[iv] [v]

According to Jonathan, two of Chaim’s sons-in-law were short time lodgers in the Schotten home: Kalman Schwarz, the husband of Chana, and Jakob Nichtburg, the husband of Helene. Both received permits to live in England. Kalman left in 1938, but Jacob waited for his wife to give birth to their fourth child; Ilse Nichtburg was born on 21 May 1939 and Jakob departed the next day.

In June 1942, Chana and her two young sons Yishai Schwarz (born 1935) and Zvi Mayer Schwarz (born 1937) became the first of the family to cross into Hungary with Chaim’s help. They joined Chana’s sister Sofia Schotten Kot who lived in the tiny village of Paks, near the Danube River about 120 km from Budapest. Helene Schotten Nichtburg and her four children followed shortly afterward.

Jakob (Yakov Meir) Nichtburg

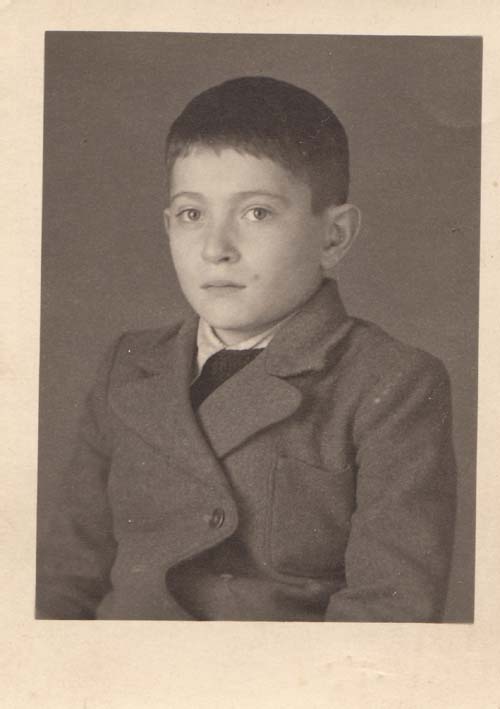

Yishai (Otto) and his younger brother Zvi Mayer Schwarz

Zvi Meyer Schwarz died in the gas chamber at Auschwitz when he was not much older than this.

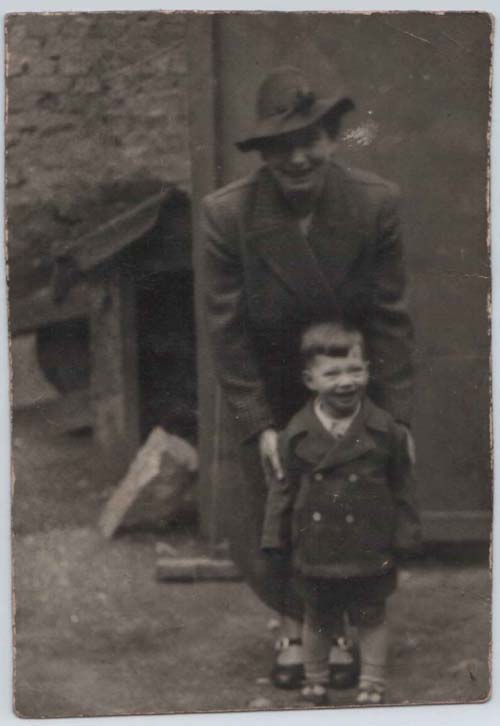

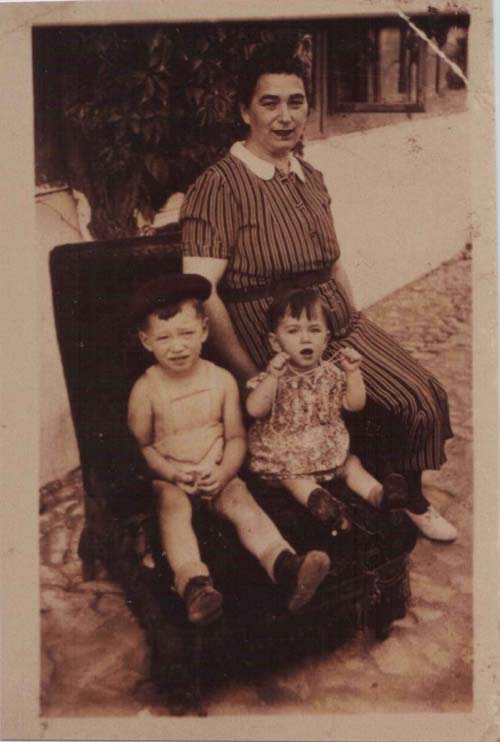

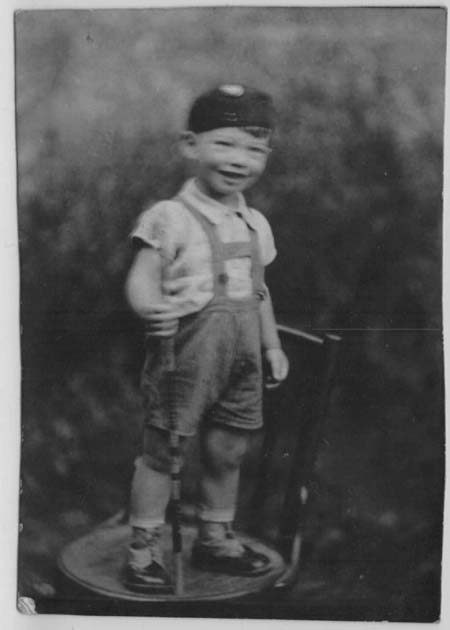

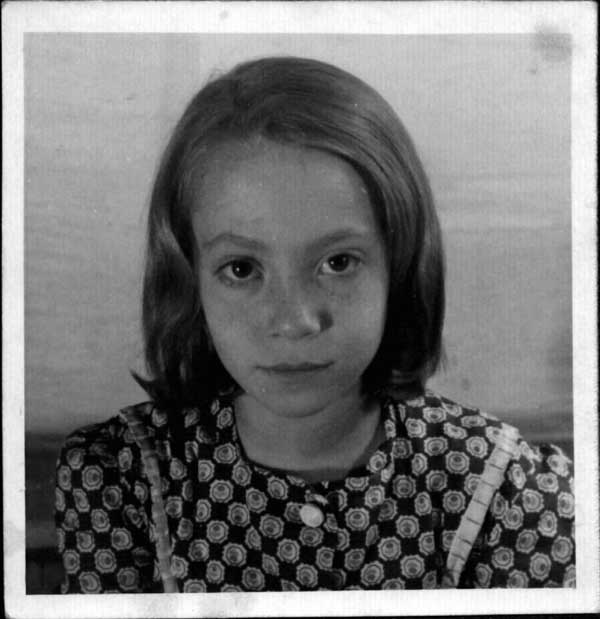

Another sister, Esther Schotten Weiss was married to the supervisor of a Jewish cemetery on the outskirts of Budapest. I later learned that his name was Sándor Weiss and that he and Esther were the parents of Tibor (Tibi) Weiss (born circa 1938) and Miri Weiss (born circa 1940).

Johanna (Chana) Schotten Schwarz

Esther Schotten Weiss

Esther Schotten Weiss, likely holding Tibi and if so the photograph was taken circa 1938.

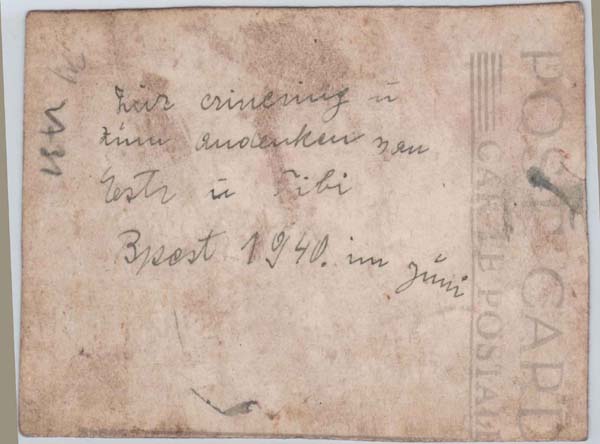

Esther Schotten Weiss and Tibi, June 1940, Budapest

Esther Schotten Weiss with her children Tibi (left) and Miri (right)

Sofia Schotten Kot was married to Rudolf Kot and they had one daughter Chana who survived infancy. The rest of their children—all girls—had died very young from some kind of congenital defect.

In October 1943, Helene Schotten Nichtburg, three of her children—David, Lici, and Ilse—and her nephew Yishai Schwarz were taken in a roundup of foreign Jews by Hungarian fascists. The Nichtburgs were placed in Szabolcs Tabor, a small internment camp inside Budapest, and Yishai was apparently placed in a ghetto elsewhere in Budapest. He has a dim memory of being cared for by Jews who worked for the Red Cross. Eventually, he was housed in a ghetto. In early 1944, Helene became so ill that she was hospitalized. After her discharge, instead of returning to Szabolcs Tabor, she rejoined her two sisters, Sofia Kot and Chana Schwarz in Paks. If this was a choice on Helene’s part, perhaps it was a fatal mistake.

In March 1944, the German Army occupied Hungary and deportations to Auschwitz soon followed. That July, all three sisters, as well as Chana’s younger son Zvi Mayer and Sofia’s daughter Chana, were deported to Auschwitz. Helene died shortly after arrival, as witnesses saw her in the line for the gas chamber holding onto the hands of small children, perhaps her niece and nephew. The fourth sister in Hungary, Esther Schotten Weiss and her family were either deported to Auschwitz or slaughtered during a massacre of Jews at the cemetery her husband tended.

Esther Schotten Weiss

This is either Esther’s handwriting or her husband’s on the back of the photograph.

Tibor (Tibi) Weiss, Budapest, August 1940

Tibi (left) and Miri Weiss in Budapest, April 1941, three years before their murder

The back of the photograph gives the date and location.

Helene’s oldest child, Gershon Baruch Nichtburg, had contracted polio when younger and it crippled one of his legs. When he came to Hungary in 1942, he enrolled in a Budapest yeshiva. After the yeshiva was shut down, he took a small job at the cemetery run by his uncle. In 1944, Gershon Baruch perished at age 13 or 14, either in the cemetery massacre or Auschwitz.

[i] Josef Weiss entry. List of Victims from Austria < DÖW online>[ii] Max Weiss, Hermine Weiss, Lea Weiss, Otto Weiss, Edith Weiss, and Judis Weiss entries. List of Victims from Austria < DÖW online>

[iii] Gitta Schotten entry. List of Victims from Austria < DÖW online>

[iv] Rosalie Holzer neé Schotten Record. List of Theresienstadt camp inmates, and Rosalie Holzer Victim entry. List of Lodz ghetto inmates. <Yad Vashem online>

[v] Heinrich Schotten record. List of Theresienstadt camp inmates. <Yad Vashem online>

Helene Schotten Nichtburg with her son, Baruch, in happier times

The Germans began emptying the Szabolcs Tabor internment camp in March or April 1944. A group of Budapest aristocrats, sympathetic to the plight of the Jewish children, took advantage of old Hungarian laws protecting orphans and placed them in orphanages. Helene’s son David Nichtburg was placed in a boys’ orphanage and her daughter Lici was sent to an orphanage for girls. Later, David was transferred to the Budapest ghetto, which was eventually liberated by the Soviet Army. David then was returned to the boys’ orphanage.

Lici survived in the girls’ orphanage, and after the war was taken by a Zionist group to Cyprus via a circuitous route. Two years later, her father Jacob Nichtburg located her with the help of the International Red Cross. Fearful of the secular influence of the Zionists on his daughter, he insisted that Lici travel alone from Cyprus to join him in England. She arrived just before Sukkot, 1947.

Ilse, the youngest of the Nichtburg children, was nearly five when her mother was hospitalized, and the girl had had been placed with foster parents. The foster parents took care of her until 1946 when the Red Cross found her, her brother David, and cousin Yishai Schwarz. After liberation, Yishai had walked from Budapest back to Paks with three friends. There they found elderly Mr. Kot, the father-in-law of Sofia, and stayed with him.

Ilse Nichtburg, postwar

Meanwhile, after their release from Theresienstadt, Chaim and Blumele Schotten returned to Vienna. In June 1946, they were reunited there with Ilse, David, and Yishai. The Schottens decided to reunite the children with their fathers in England. Along the way they visited their son Ignatz in Switzerland, where he had survived the war, and their eldest daughter Rosa in Paris (the daughter I hadn’t known about). In happier times, Rosa (Chaya Sara) Schotten had married a distant cousin, Simon Österreicher. They fled to France in 1938 with their three children Yolanda (Jolan) (Yehudit Laviah), Hedwig (Chana), and Erich (Moshe). The family hid in Lyon and Marseille, even finding refuge at one point in a Catholic Church. All survived the war and settled in New York.[i]

![The surviving Nichtburg children and their father, March 25, 1948. This photo was taken a couple years after the family reunited in England. Jakob Nichtburg [far left] with Alice (Lici) [standing] and Ilse and David (Dudi) [sitting].](http://carolegvogel.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Jakob-Nichtburg-Ilse-Lici-Dudi-25-03-48-web.jpg)

The surviving Nichtburg children and their father, March 25, 1948. This photo was taken a couple years after the family reunited in England. Jakob Nichtburg [far left] with Alice (Lici) [standing] and Ilse and David (Dudi) [sitting].

Kalman and Yishai Schwarz, December 2, 1948, two years after they were reunited.

When it was certain that his wife had not survived the Holocaust, Kalman Schwarz took a new wife, Miriam.

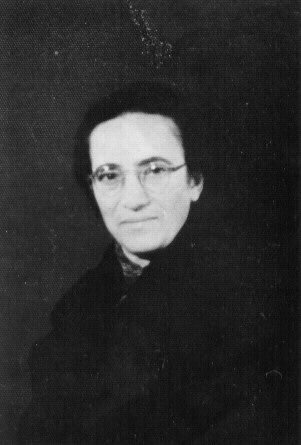

Rosa Oesterreicher née Schotten.

Chaim and Blumele were reunited not only with their daughter Rosa Österreicher and her family, but with yet another grandchild—Hashy Lipshütz—the son of Malvine. Hashy had survived in Italy. The Schottens prevailed on him to take David and Ilse Nichtburg and Yishai Schwarz to England as the Schottens didn’t have a permit to enter the country. Neither did Hashy but in August 1946 he sailed with the children to Dover, England, where they were reunited with their fathers, and Hashy was sent back to France. Years later, the cousins Ilse and Yishai married each other and had four children. Lici (Alice) Nichtburg married Leibl Gelkopf and became the mother of two sons and five daughters. David changed his name to Burg, married, and had one son, Jonathan, who was able to complete the family history for me. Hashy stayed in France and married somebody out of the faith. He died before his Uncle Ignatz, who died in 1966.

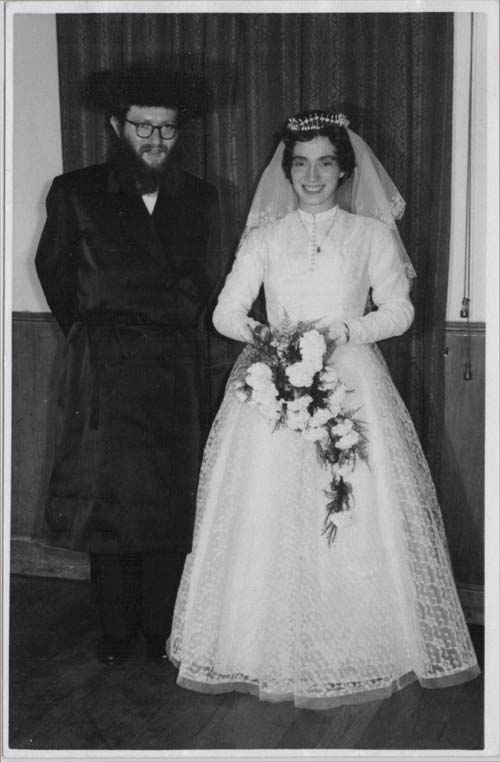

Yishai Schwarz and Ilse Nichtburg on their wedding day.

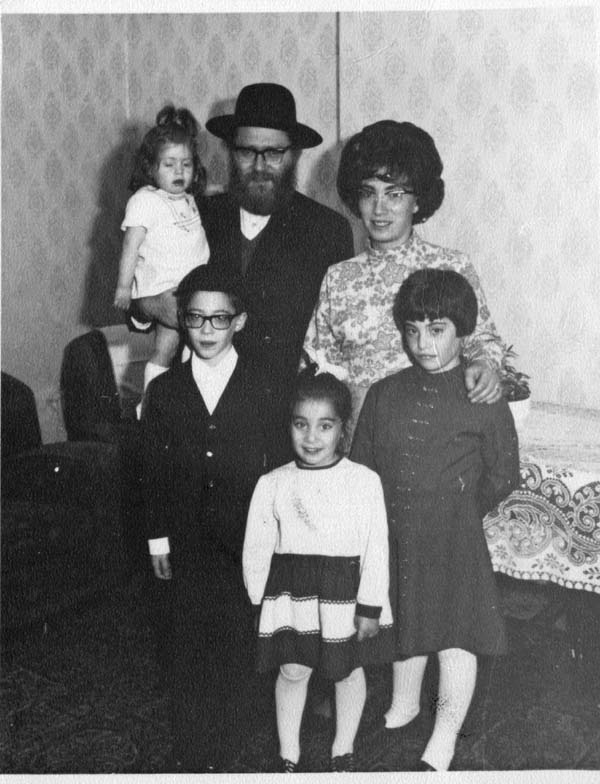

Yishai and Ilse Schwarz and their children.

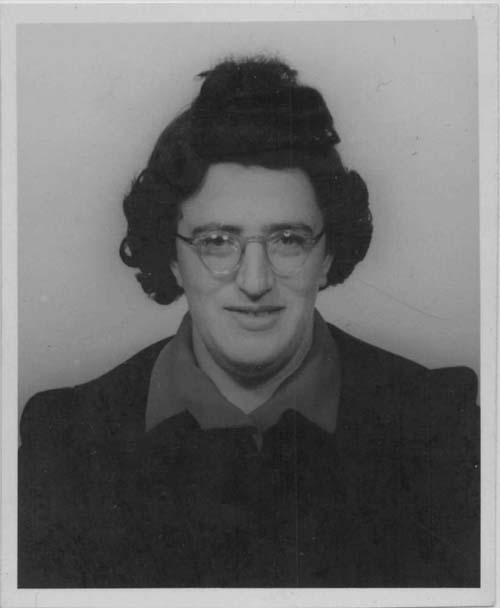

Ilse Schwartz nee Nichtburg, sometime in the 1960s in England.

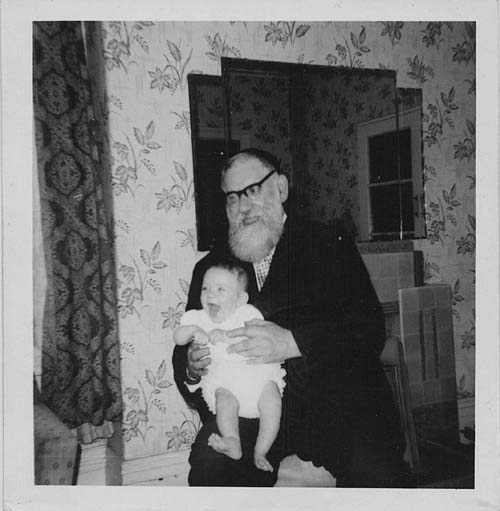

Lici Nichtburg married LeiblGelkopf in 1955

The bride Lici Nichtburg sitting next to her aunt Anna Balkind née Schotten, 1955.

I learned from Jonathan that Anna, the second youngest of the Schotten children, had escaped Hitler’s deadly net in 1938 by getting a permit to live in England. There she married Rabbi Yonah Balkind and raised three children. Sometime in 1946, Chaim and Blumele moved into Anna’s home in Manchester but she could not support them. So eventually for economics reasons, the Schottens moved to the United States, where their son Sigmund had settled before the Holocaust.

Anna Balkind née Schotten 31 Aug 1947.

Wedding of Jonah (Yonah) Balkind and Anna Schotten, June 4, 1942. To the left of the groom is David Nichtburg, and to the left of him is Kalman Schwartz.

Yonah Balkind, 16 Jun 1967

Chaim and Blumele sailed on the on the S.S. Queen Mary and arrived in New York on 6 April 1948, and moved in with Siegmund and his wife Cacilla (Tzilia) and their son 11-year-old son. They were soon joined in America by their daughter Rosa Schotten Österreicher and her family. The Goldberger’s son Ignatz, who never married, left Switzerland and also established himself in New York. He traveled by plane, arriving on 26 Nov 1948.

Jakob Schotten, the eldest son, had lived in Wiener Neustadt on Kammerbach-gasse, 29. In spring 1938 he was arrested and sent to Dachau Concentration Camp. He arrived there on June 25, 1938 and was transferred to Buchenwald on September 23, 1938. Somehow, his release was secured and he was allowed to leave Buchenwald. He was told to the leave the country within 24 hours or be else he would be arrested again. His wife Ilonka had already fled to Italy with their three daughters Pnina, Helga, and Lisa. She must have obtained exit papers and train tickets for Jakob because he joined them in Italy, south of Rome. The family was arrested after the German occupation of Italy and but they were released and all survived the war. Jakob had health problems though and died in Switzerland during heart surgery in 1949. It was his daughter, Pnina, who had settled in Jerusalem and submitted pages of testimony to Yad Vashem for his siblings. Jakob’s other daughters also settled in Israel.

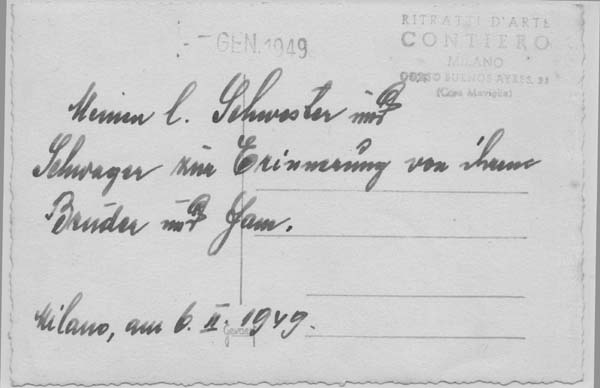

Jakob Schotten and Ilonka with two of their daughters, Lesl (left) and (Helga (right), February 6, 1949 in Milano,Italy . The photograph was inscribed by Jakob on the back and sent to his sister Anna Schotten Balkind in England.

Ilonka Schotten (top) and her daughter Lisl (second row from bottom far left) visited the Balkinds in 1956.

By the mid-1950s, Blume and Chaim had both died of natural causes. They were unable to see their family rebuild itself. Now more than fifty years later there are dozens of Schotten descendants living just in New York City alone.

[i] Telephone conversations with Rosa’s grandson, Mendy Oesterreicher of Brooklyn, NY, 2005.

Heinrich Schotten after the war

Betti Goldberger Schotten after the war

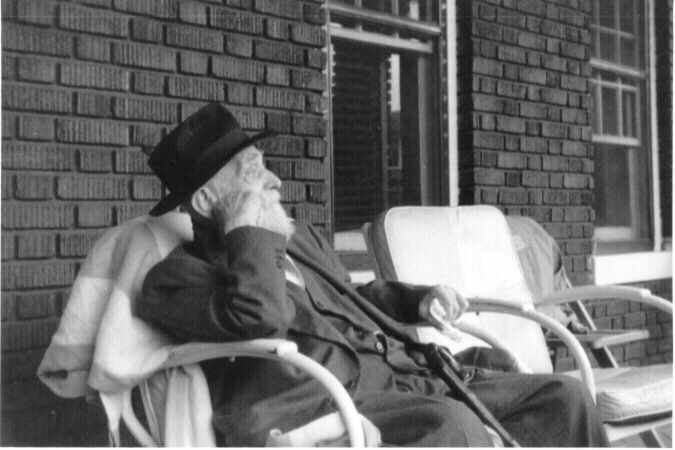

Chaim Schotten near the end of his life.

Headstones of Chaim (left) and Blumele Schotten (right).

Rosa’s daughter Jolan married in Lyon, France in 1947 and settled in New York.

I spent more than 30 years trying to find the remnants of the Goldberger-Schotten family but it never occurred to me to look in my own backyard in Lexington, Massachusetts, or more precisely in the two towns abutting my own—Burlington and Bedford. I must have passed the Pass and Weisz Porsche and Audi dealership hundreds of times without stopping into inquire about possible family relations, even though I often noted that Weisz was a family name of interest. If I had made the effort, I would have discovered that the owner was Ottfried (Fred) Weiss, the son of Irma Marie Schotten and Deszö (Desiderius) Weisz.

I only made the connection after I finally tracked down Jonathan Hall, the person who had sought information about Irma Schotten on Ancestry.com. He had posted a family tree on Ancestry that contained Heinrich Schotten but access to the information was blocked for privacy reasons. I was able to send Jonathan a message and the story soon unfolded.

When Fred Weisz was about ten, he fled Vienna with his parents and sister and went to Italy. All four were arrested in a roundup of Jews conducted by Italian policemen at the instigation of the German occupiers. One of the policemen clearly had a distaste for the roundup. That night he returned to the prison in civilian clothes and smuggled Fred out and placed him in a Catholic orphanage. The priest in charge of the orphanage treated Fred cruelly but did not turn him over to the authorities. Fred survived the war and afterwards learned of the murders of his parents and sister. He made contact with his uncles Ignatz and Jakob Schotten, moved to Israel, and served in the Israeli Army for three years. Afterward, he immigrated to the United States, where he was drafted into the U. Army to fight in the Korean War. Instead, he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force for four years and became an airplane mechanic. It was his skill with engines that eventually paved his way to owning a car dealership. Fred by his own account had a great time in the Air Force.

Fred had made the decision to disguise his Jewish roots and he married a Christian woman. Ignatz and the other Schottens in New York disapproved of the marriage and disowned him. Fred and his wife had two daughters, Vickie and Jennifer. He raised the girls as Protestants and never revealed that he had been born a Jew. The girls didn’t learn about their Jewish heritage until they reached their twenties and that was when they also discovered that their maternal grandparents and aunt had been murdered because they were Jewish.

The daughters grew up in Bedford, in walking distance of my house. Vickie Weisz married Jonathan Hall and moved to Vermont. Jennifer Weisz married Steve Hartwell and now lives in New Hampshire. Fred sold his car dealership and retired to Florida. In 2008, Jonathan Burg visited Boston and I arranged a mini-family reunion for Jonathan with me, Jennifer, and our husbands.

Fate of the Family of Katalyn Goldberger and Salamon Pollack

The second of the known children of Johanna Österreicher and Jakob Goldberger was Katalyn Goldberger. I could not find Katalyn or her husband, Salamon Pollack, in any of the records of Austrian victims, but from their marriage record I knew that Salamon had been born in Pozsony (Bratislava), Czechoslovakia, in 1883. I also knew that Jews had been desperate to flee Nazi Austria, so I had hunch that Salamon and his family had returned to his hometown during the Shoah. This proved correct. A Salamon Pollak, born in Galanta, Bratislava in 1883, and his wife Katarina Pollack born in 1879 in Papa, Hungary, were deported from the Zilina transit station in Czechoslovakia to Auschwitz on 24 Jul 1942.[i]

Deported to Auschwitz from the same location exactly one week earlier was a Jakob Pollak, together with his wife, Hermina, and their young sons Henrich Pollack (born 1933) and Siegfried Pollak (born 1938).[ii] An entry in the Death Books from Auschwitz: Remnants showed that Jakob Pollak (born in Rajka, Hungary on 21 Mar 1908) was the son of Salamon Pollak and Katherine Goldberger.[iii]

Hermina and the boys were probably gassed close to their arrival in Auschwitz but Jakob survived for two months, dying on 24 Sep 1942. I don’t know whether Jakob had any siblings or not. Since no one left a Page of Testimony at Yad Vashem for any members of this family, it is likely that if Jakob had siblings, they were killed too.

[i] Salamon Pollack and Katrina Pollak Deportation Records. Based on deportation lists. Ústredný Archív Slovenskej Republiky v Bratisl, Fond: Ministerstvo vnútra SR (1938-1945), Kartotéka Źidov Na Slovensku, Kartón č. Slovakia Holocaust Jewish Names Project, Commenius University of Bratislava, Dept. of History, Bratislava. <Yad Vashem online>[ii] Jakob Pollak, Hermina Pollak, Henrich Pollak, and Siegfried Pollak Deportation Records. Transport from Zilina to Auschwitz on 17 Jul 1942. Prisoner numbers 28-31. <Yad Vashem online>

[iii] Jakob Pollak Victim Record. Auschwitz Death Registers. Source page number: 32506/1942. <Yad Vashem online>

Simon Goldberger, His Wife and Daughters

The last of the known children of Johanna Oesterreicher and Jakob Goldberger was Simon Goldberger. I first learned about him from Joseph Spiegel’s sister Olga Spiegel Fleisher, who remembered Simon and his family from her childhood in Vienna. “I knew the family well,” she wrote me. “His two daughters were very good friends of [your grandfather’s sister] Frieda Löwy Sipser. One daughter was a religion teacher who married a music teacher. The other one married Herr Siegel, the owner of a printing and publishing company called Jahoda und Siegel. This company published the ‘Fackel’ by Karl Kraus.” Olga also recalled that Simon was a tailor and that he had survived Theresienstadt concentration camp.[i]

From Theresienstadt records, I learned that Simon Goldberger was born on 24 Aug 1871 in Kobersdorf, Austria, and during wartime had lived at Judenplatz 8 in Vienna’s first district. He was transported to Theresienstadt Concentration Camp on 25 September 1942, and managed to live to be liberated.[ii] My trip to Vienna in September 2005 filled in more details. Meldezettel (household registration records) showed that Simon was a Vienna resident from 10 Aug 1904 until deportation to Theresienstadt on 24 Sep 1942. [iii] His wife, Johanna Breuer Goldberger died in the city on 15 Sep 1941. Their children were Rosa (born 1899) and Erna (born 1900). Rosa had married Israel Reiss.[iv] She was deported to Theresienstadt on the same transport as her father, but on 4 Oct 1944 she was sent to her death in Poland.[v] Until, the summer of 2009, I did not know the fate of her husband, sister, or any possible children. Then through immigration and other documents posted online at Ancestry.com, I was able to pieces together information Erna’s fate.

Erna had married Konrad Siegel, a teacher born in Vienna in 1901, and had two daughters—Rita Siegel (born 1930) and Elly Siegel (born 1932). Konrad was arrested by the Nazis and sent to Dachau Concentration Camp, where he was detained for nearly four months from June 3 to September 23, 1938 and then released.

About six months later, the family obtained the necessary visas to immigrate to America. On March 4, 1939, they departed Flushing, Netherlands on the S.S. Ilsenstein, and arrived at the port of New York on March 17. Their destination was a cousin, Mrs. V. Schwabacher who lived in Brooklyn, New York. I do not know how Mrs. Schwabacher is related and can’t even fathom a guess because I don’t know her maiden name.

By the time Konrad applied for U.S. citizenship in June 1944, he had changed his name to Fred Conrad Siegel and the family was living on Wadsworth Avenue in New York City. Fred died in 1981and Erna died three years later.

I have not been able to track Rita Siegel but her sister Elly submitted a Page of Testimony for her maternal aunt, Rosa Goldberger Reiss. Elly used her married name—Elly Herman. The address she gave was for a town almost in my backyard—Newton Centre, Massachusetts—about 25 minutes from my home. I also discovered that she had written to the New York Times in 1982, and in it she mentioned that she was the mother of three.

So my quest to reconstruct the family is not quite over.

[i] Letter from Olga Fleisher to C.G. Vogel; 18 Jun 1991.[ii] Simon Goldberger entry. List of Theresienstadt camp inmates. Based on documents from Terezinska Pametni Kniha/Theresienstädter Gedenkbuch, Terezinska Inciativa, vol. I-II Melantrich, Praha 1995, vol III Academia Verlag, Prag 2000. <Yad Vashem online>

[iii] Simon Goldberger household registration records (Meldezettel), Magistratsbteilung 8, Wiener Stadt und Landesarchiv, Vienna.

[iv] Israel Reiss-Rosa Goldberger’s marriage record, IKG-Wien marriage records for 1923.

[v] Rosa Reiss Record. List of Theresienstadt camp inmates. <Yad Vashem online>

[1] Gizella Schotten death record. Date of death: 4 Mar 1916. Age: 2 (born circa 1912). Birthplace: Mattersdorf. Place of death: Mattersdorf. Parents: Heinrich Schotten and Betti Goldberger. Cause of death: göresök [görcs means spasm]. Death reported by her mother on 5 Mar. Nagymárton death registrations 1902-1920, FHL microfilm 0700405, p. 2 entry 11. [Researched by CGV 2006]

[2] Letter from Joseph Spiegel; St. Louis, MO to C.G. Vogel17 Dec 1990.

[3] Emanuel Lipshütz entry. Death Books from Auschwitz: Remnants. Reports edited by State Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau. (München: K.G. Saur, 1995.), p. 14682/1942. <Yad Vashem online>

3 Malvina Lipschutz née Schotten entry. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum French Deportation List, p. 58, line 109. < USHMM online>

[5] Vera Lipshütz entry. Memorial de la deportation des juifes de france by Beate et Serge Klarsfeld, Paris: 1978. Transport 30 from Drancy to Auschwitz. <Yad Vashem online>

[6] Vera Lipshütz and Malvine Lipshütz neé Schotten Pages of Testimony. Submitted by Herma Migliavacca neé Lipshütz <Yad Vashem online>

[7] Helene Nichtburg neé Schotten entry. List of Victims from Austria. Namentliche Erfassung der österreichischen Holocaustopfer Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes, DÖW, Wien. <DÖW online>

[8] Helene Nichtburg neé Schotten Page of Testimony submitted by Pnina Horowitz neé Schotten, 1999. <Yad Vashem online>

[9] Beno Nichtburg entry. List of Victims from Austria < DÖW online>

[10] Irma Weisz neé Schotten Page of Testimony submitted by Pnina Horowitz neé Schotten, 1999. <Yad Vashem online>

[11] Dezö (Desiderius) Weisz and Hilda Weisz Pages of Testimony submitted by Pnina Horowitz neé Schotten, 1999. <Yad Vashem online>

[12] Irma Weisz neé Schotten entry. German Jews at Stutthof concentration camp listing. <JewishGen Holocaust Database Online>

[13] Irma Weisz neé Schotten Page of Testimony <Yad Vashem online>

[14] Janka Schotten Page of Testimony <Yad Vashem online>

[15] Johanna Schwartz entry. List of Victims from Austria. < DÖW online>

[16] Esther Schotten Page of Testimony <Yad Vashem online>

[17] Josef Weiss entry. List of Victims from Austria < DÖW online>

[18] Max Weiss, Hermine Weiss, Lea Weiss, Otto Weiss, Edith Weiss, and Judis Weiss entries. List of Victims from Austria < DÖW online>

[19] Gitta Schotten entry. List of Victims from Austria < DÖW online>

[20] Rosalie Holzer neé Schotten Record. List of Theresienstadt camp inmates, and Rosalie Holzer Victim entry. List of Lodz ghetto inmates. <Yad Vashem online>

[21] Heinrich Schotten record. List of Theresienstadt camp inmates. <Yad Vashem online>

[22] Salamon Pollack and Katrina Pollak Deportation Records. Based on deportation lists. Ústredný Archív Slovenskej Republiky v Bratisl, Fond: Ministerstvo vnútra SR (1938-1945), Kartotéka Źidov Na Slovensku, Kartón č. Slovakia Holocaust Jewish Names Project, Commenius University of Bratislava, Dept. of History, Bratislava. <Yad Vashem online>

[23] Jakob Pollak, Hermina Pollak, Henrich Pollak, and Siegfried Pollak Deportation Records. Transport from Zilina to Auschwitz on 17 Jul 1942. Prisoner numbers 28-31. <Yad Vashem online>

[24] Jakob Pollak Victim Record. Auschwitz Death Registers. Source page number: 32506/1942. <Yad Vashem online>

[25] Letter from Olga Fleisher to C.G. Vogel; 18 Jun 1991.

[26] Simon Goldberger entry. List of Theresienstadt camp inmates. Based on documents from Terezinska Pametni Kniha/Theresienstädter Gedenkbuch, Terezinska Inciativa, vol. I-II Melantrich, Praha 1995, vol III Academia Verlag, Prag 2000. <Yad Vashem online>

[27] Simon Goldberger household registration records (Meldezettel), Magistratsbteilung 8, Wiener Stadt und Landesarchiv, Vienna.

[28] Israel Reiss-Rosa Goldberger’s marriage record, IKG-Wien marriage records for 1923.

[29] Rosa Reiss Record. List of Theresienstadt camp inmates. <Yad Vashem online>