Oswego, New York: Wartime Haven for Jewish Refugees

by Carole Garbuny Vogel

published in Avotaynu, winter 1998

IN 1965, WHEN I WAS 14 YEARS OLD and hunting for a tennis racket in the garage, I came across a battered suitcase with a treasure trove of letters inside. My father had saved every letter written to him in his bachelor days, including love letters from my mother. In addition he had saved carbon copies of every letter he had written back. I quickly put all thoughts of tennis out of my mind, sat down on the cold cement, and began to read. I had gone through ten or so letters when I found one from my mother written in 1944, describing her joy at learning that her Tante Frieda and Onkel Max were alive and well in a detention camp in Oswego, New York.

Frieda Löwy Sipser and her husband Max (on right) are visited in August 1945 by her sister, Elsa, and her husband Max Gansl at Fort Ontario, a detention camp in Oswego. New York, where the Sipsers were held from August 1944 until January 1946.

Immediately I raced upstairs to question my mother. What were Tante Frieda and Onkel Max doing in jail? And why were you happy about it? My questions were met with a wall of fury, and mother lectured me about invasion of privacy. She confiscated the letters and placed the suitcase out with the trash.

I should have known better than to approach my mother. In 1938, she had fled her home in Vienna. After finding refuge in a flat in Paris and later in London, she moved to New York in 1939. A few years later she met my father, a refugee from Berlin, and eventually they began to date. During their early years of courtship, much of their focus had been on who among their friends and relatives had survived Nazi tyranny and who had not. The news was mainly grim, and my parents’ willingness to discuss these matters had disappeared by the time I was a teenager and curious about the family history.

Frieda before World War II

Perhaps Tante Frieda Löwy and her husband, Max Sipser, would have been more forthcoming but I never really got to know them. Max died in 1968, and Frieda passed away in 1979, a few months before I became interested in genealogy. When I was a child, I had seen Max and Frieda at Passover seders, but their broken English was too hard to understand, and I was more interested in playing with my cousins. Frieda was the youngest of my grandfather Moriz Löwy’s four siblings. She had been born in 1900 in Gloggnitz, Austria, graduated from the Konservatorium of Music in Vienna, and became a piano teacher. Before the Anschluss, Frieda lived with my grandfather and his family in Vienna.

About a dozen years after Frieda’s death, I visited the New York State Museum in Albany. By chance, there was an exhibit about a World War II detention camp for Jewish refugees in Oswego, New York. Although I had long forgotten about Frieda and Max’s connection to Oswego, I must have remembered it at a subconscious level. I was overpowered by the exhibit and found myself crying as I walked through it.

The exhibit told of one of the few acts of kindness that the United States had bestowed upon Jewish refugees during the Shoah. The Untied States, like the other nations of the world, had turned its back on the Jews trapped in Hitler’s Europe. American consulates in Europe told the Jews the quotas were filled. (Under U.S. law only 3,900 refugees were permitted to enter the United States each month and the waiting list was tremendous.) However, in 1944, President Roosevelt decided that 1,000 refugees should be brought immediately from Italy. The following notice was posted there in English and German:

Displaced Persons Sub-Commission

Allied Control Commission

Notice And ApplicationJune 20, 1944

The President of the United States has announced that approximately one thousand non-Italian refugees will be brought to the United States from Italy. The refugees will be maintained in a refugee shelter to be established at Fort Ontario near Oswego in the State of New York, where under appropriate conditions they will remain for the duration of the war. The refugees will be brought to the United States outside the regular immigration procedure The shelter will be equipped to take good care of the refugees and it is contemplated that they will be returned to their homes at the end of the war.

It is planned to select and move applicants for this refugee shelter as soon as possible. Preference will be given to those refugees for whom no other haven or refuge is immediately available. Therefore, if you desire to make application for admission please fill out the form below. Please use only one form for yourself and all members of your immediate family. Notification of acceptance for movement will be given as quickly as possible after your applications has been received.

Three thousand desperate people in Italy applied for passage. One thousand were selected from 18 different countries, among them were Frieda and Max. Nine-hundred eighty-two refugees actually sailed, of which 108 were not Jewish as President Roosevelt did not want the rescue mission to be perceived as a Jewish project.

Frieda and Max applied the day the notice was posted and were accepted. He was assigned the refugee number 848 and she was given number 849. On the 20th (or so) of July, they boarded their rescue vessel, the Liberty ship Henry Gibbons in the Bay of Naples. On board, in addition to the refugees were wounded American soldiers. The Henry Gibbons was part of a convoy of 16 troop and cargo ships escorted by 13 warships. Two ships carrying Nazi prisoners of war ran parallel to the Henry Gibbons as protection against Nazi attack. At night, all the ships observed a black out so they could not be detected in the darkness.

The trip through the Mediterranean Sea was fraught with danger. Nazi bombers and U-boats were a constant threat. During the third night at sea, Nazi planes were detected overhead but they did not attack the flotilla. The next night at 1:00 a.m., the ship’s sonar detected a U-boat and the refugees were asked to maintain absolute silence. The engines of all the ships were shut off and the U-boat was unable to track the fleet. The danger passed and the all clear signal was given.

On August 3, the Henry Gibbons sailed into Pier 84 in the Port of New York. None of the refugees were permitted to disembark. They spent the night on the ship and the next day the men and women were led to a hut on the wharf where they were separated. The refugees were ordered to remove all their clothes and march in front of American soldiers who sprayed them from head to toe with DDT to disinfect them. Their clothes were put into a chamber, disinfected, and then returned.

The refugees had no legal status under American law. The Justice Department refused to permit them to register as aliens under the Alien Registration Law. They were homeless and stateless. Even Nazi prisoners of war had more legal standing. The government had decided to house the refugees for the duration of the war with the intention of returning them to their own countries when the war ended. The refugees had all signed documents agreeing to their eventual return. Instead of passports, the refugees were given cardboard identification tags to wear around their necks. The tags were labeled, “U.S. ARMY Casual Baggage” and each had an identification number—not a name.

The refugees were transferred to two harbor ferries that took them across the Hudson River to Hoboken, New Jersey, and the terminal dock of a railroad line. Guarded by 100 MPs (military police), the refugees were not permitted to contact any of their friends and relatives in America, as a war precaution. However, a press conference was allowed where a selected group of refugees told reporters their tragic stories.

All the refugees then boarded a train for Fort Ontario, a former army camp on Lake Ontario in Oswego, New York. The refugees were shocked when they saw that their new home was to be an internment camp surrounded by a tall chain-link fence with three rows of barbed wire at the top. For survivors of Nazi concentration camps and labor camps, this was quite a blow.

They were placed under quarantine for four weeks—no refugees were permitted to leave the camp and visitors were not allowed. To Americans of today it should come as no surprise to learn that Fort Ontario had been placed under the jurisdiction of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) of the Department of the Interior, the same agency that oversaw the tragic relocation of Japanese-Americans from their homes to ten internment camps after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese.

The camp itself was huge, it covered 80 acres and touched the shore of Lake Ontario. The refugees were housed in white, wooden barracks furnished in Army fashion—metal cots, tables and chairs, and metal lockers. The WRA furnished the basic comforts of life—such as sheets and pillows, but Jewish and Christian relief agencies provided other items such as cribs, high chairs, window curtains, and shower curtains.

On September 1, the camp held an open house where visitors and townspeople could tour the facilities and meet with the refugees. With the lifting of the quarantine, the children were permitted to leave the camp to attend school, and later adults were permitted to take day jobs in town. However, the refugee were required to return each night to the camp.

On December 22, 1945, President Truman (who had assumed the presidency after Roosevelt’s death) announced that while he would not recommend increasing the quota, he would make it possible for the Oswego refugees to enter the United States under current immigration laws. Beginning on January 17, 1946, refugees were bused to Niagara Falls, Canada, given a visa by the American consul and then permitted to cross the Rainbow Bridge and enter the United States and apply for citizenship.

I did not make the conscious connection of Frieda and Max Sipser’s link to Oswego until a few years after I had toured the museum exhibit in Albany. A distant cousin who was helping me compile the family history asked why I had not included the Sipsers’ Oswego experience in my account. She had remembered visiting them there.

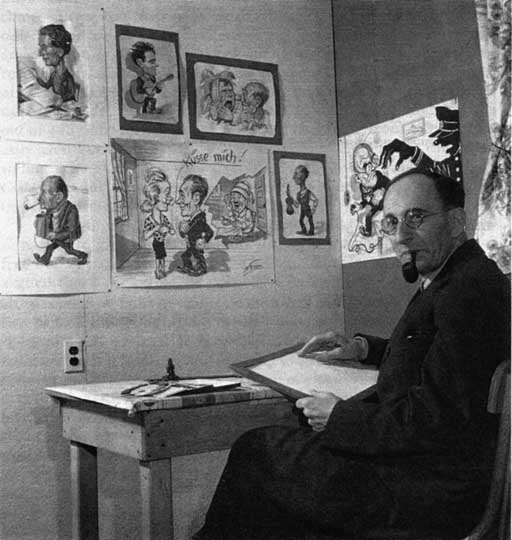

Max at his desk where he created cartoons for the weekly edition of the camp newspaper

Suddenly everything clicked and I set out to read everything I could about the camp, including Haven by Ruth Gruber (Coward-McMann, 1983) and Token Refuge by Sharon R. Lowenstein (Indiana University Press. 1986). In Lowenstein’s book I found a photograph of Max with the caption: “Fifty-one-year old Max Sipser, a graphic artist and caricaturist from Austria, resumed work with a cartoon in each week’s Ontario Chronicle [the camp newspaper].” According to Lowenstein, Max also gave painting lessons to other refugees in the shelter. He taught at least one person how to paint miniatures in water color, and Frieda gave piano lessons in the camp.

Lowenstein’s bibliography pointed me in the direction of the National Archives, where case files for the individual refugees were held. I requested Max and Frieda’s files from the Emergency Refugee Shelter Refugee Case Files collection, Record Group RG 210. Location 1E2 36/23/5, box 24, and WRA Central File No. 41.145J Refugee Shelter #3, May 1945; pp. 848-849. Location 1E2 34/14/4 Box 301 (first folder in file box). Civil Reference Branch, Code NNRC Floor 11E, National Archives Records Administration, 7th and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20408.

A copy of the records cost me $13.50. For that fee, I learned everything my mother had refused to tell me about Max and Frieda when I was 14 years old. In a report of an interview with the Sipsers on December 8, 1944, the interviewer noted that:

Mr. Sipser [age 49] stated that he has no health problems. However, we noticed a nervous blinking of his eyes. It might be that he is suffering from a nervous condition, which he does not want to admit. At this time, Mrs. Sipser [age 44] is a pale-looking woman. She has rheumatism… The walls of [the Sipsers’] clean and well-kept apartment were covered with drawings and pictures made by Mr. Sipser in Italy and in Oswego. Mr. and Mrs. Sipser stated that they were very much satisfied with their present living conditions because they have now again decent food, normal beds, and well-heated and clean rooms… It’s this couple’s desire to remain in the U.S. They consider themselves as too old for immigration to Palestine; in addition their relatives in Palestine wrote them that they will not be able to maintain themselves there being a painter and a musician. They strictly refuse to think in terms of return to Austria from where they were expelled under humiliating conditions.

The records also provided an extremely detailed account of the Sipsers’ lives before coming to Oswego. Max had been employed by a film company after serving in the Austrian infantry during World War I. He then opened his own enterprise—a studio for posters, advertisements, and trick films. Shortly after the Anschluss, Max was arrested and sent to Dachau concentration camp for one month and then released. On July 19, 1938, Max and Frieda applied for a visa at the American Consulate.

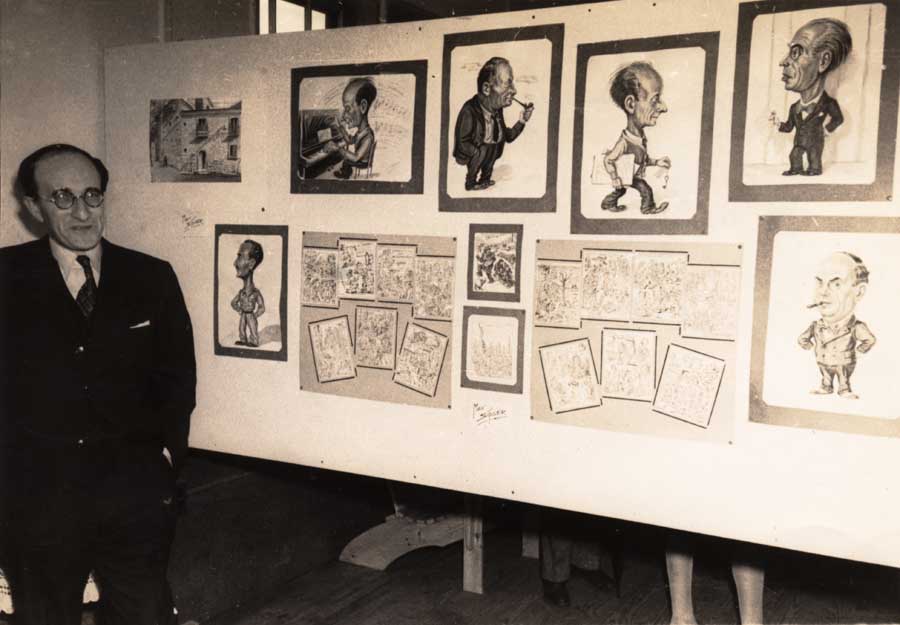

exhibition

Max at an exhibition of his work at Fort Ontario

They married in February 1939, and in July of that year, fled to Milan, Italy. At that time, Italy was a neutral country, although it was politically close to Germany. The previous November (1938), under pressure from Hitler, the Italian dictator Mussolini had enacted anti-Jewish laws. More than 10,000 Jewish refugees from Austria and Germany had sought refuge in that country. The Italian government did not have the taste for antisemitism that the Nazis had, however, and it resisted German demands to deport the Jews.

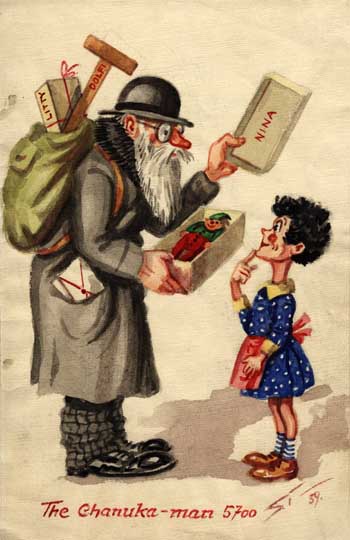

Close-up of one of Max’s caricatures

On June 10, 1940, Italy declared war on Great Britain and France, and the next day the Italian police began to arrest foreign Jews. Susan Zuccotti, author of The Italians and the Holocaust: Persecution, Rescue, and Survival (Basic Books, 1987, p. 53) writes, “Although Italy was officially a racist country, the primary purpose of the arrests of foreign Jews was not to persecute them as Jews but to intern them as presumably anti-Axis refugees.”

A month later, Max was arrested and sent to an Italian internment camp in Alberobello (Bari), where he remained until January 1941. He was transferred to a work camp in Ferramonti, in the province of Cosenza, Italy. Frieda, who had remained free in Milan, was sent there at the same time. She may have joined Max voluntarily, for it was not uncommon for women and children left without economic means to join their men voluntarily in Ferramonti. The conditions were bad but not as terrible as those in the Nazi labor camps or concentration camps. The Sipsers remained in Ferramonti for eight months and then were sentenced to “free confinement” in the town of Archi (Chieti) for two-and-a-half years (October 1941 to January 1944). According to Zuccotti (p. 54), the Italian government maintained a second system of detention in which individuals were held under light surveillance in private houses in small villages and expected to report to the police regularly.

Max drew this cartoon for the children of Frieda’s brother Moriz Löwy in 1939 in Vienna, when he still had access to color paints.

According to an interview Max gave on December 8, 1944, they underwent many hardships during the time of the German occupation of Italy, beginning in September 1943, when they went into hiding in Archi to escape the German Army. He gave no details about their time in hiding but I surmise that Frieda, who had Sephardic features, could have passed easily as an Italian and moved freely in public. Max, however, looked more like the stereotype of an Askenazai Jew and could not be seen in public. The Sipsers were sent to a transit camp in Bari from February to April 1944 and later to Santa Maria di Bagni from April to July 1944.

After I read the official account of the Sipsers’ experiences in Italy, I realized that they could not have survived while in hiding without the help of Italian Catholics. I wrote to the U.S. Embassy at the Vatican, asking advice on how to track down the Sipsers’ benefactors. The Embassy sent me the name and address of Don Angelo Vizzarri, the parish priest in Chieti. I then sent the priest photographs of the Sipsers and asked him to post a notice in his parish asking if anyone remembered the couple. A few months later I received this reply:

We have gathered some information through families of our little town, and it results that Max and Frieda Sipser of Jewish origin spent their days of forced relegation in Archi from 1941 to 1944. They used to live in an apartment situated in Via Palazzo 10, which belonged to Maria and Angela Giovanelli. Everybody who met Max and Frieda during these days has a very pleasant memory of them. They were a reserved, gentle, and friendly couple. Boys who used to visit them loved to be portrayed by Max, who as he lacked colors (due to wartime) drew his portraits in charcoal. Max and Frieda loved to take long walks along the beautiful road which lead to Tornareccio, always accompanied by their dog named “Bak” (a boxer). The families who supported Max and Frieda Sipser during these days were the Carpineta family, Silvio, the then Podesta (parish priest?), and Doct Vincenzo, Totaro Raffaele, and Caterina Lannutti, owner of a local tavern. [The Sipsers] were highly esteemed by the people of Archi and their leaving deeply affected their friends.

Don Angelo Vizzarri also enclosed some pictures of Archi and a long letter from Anna Lannutti who had lived next door to the Sispers. Anna’s father was a tailor and Frieda had helped him in his shop. There, Frieda mended clothes and wove purses and belts from straw which she sold at very low cost. According to Anna:

The citizens had so much respect for this couple and knowing that they were refugees, they offered them our local produce… I have always had a wonderful memory of them because the woman gave me one of the belts that she made. I treasure this gift so much that I care for it like a little jewel and I have worn it for an extremely long time.

More than 75 members of Frieda’s family perished in the Holocaust, including her mother Franziska Löwy (nee Kohn), who died of starvation and typhus in Theresienstadt concentration camp. Max’s brother Wilhelm Sipser, and sister Toni Sipser, and presumably many others of his relatives were among the six million who perished. If it were not for the compassion of some of the citizens of Archi, Frieda and Max would be among these grim statistics.